A brief history of SOX

At its core, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX or the Act) is a law that was enacted in 2002 to protect the investing public.

Leading into that year, there were a rash of corporate scandals that involved the likes of Enron, WorldCom, (etc.). Massive amounts of investor money was lost in the capital markets. Everything was questioned, and accounting giant, Andersen fell as a result.

Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., Senator Paul Sarbanes and Representative Michael Oxley worked on separate bills to clean up corporate accountability and transparency and increase auditor accountability and responsibility. These two bills were ultimately combined and presented to Congress as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.

Both houses voted on and approved the Act – without change – on July 24, 2002: 423 to 3 in the House, and 99 to 0 in the Senate. Then-President George W. Bush signed it into law on July 30, 2002.

Basic SOX

The Act itself is comprised of 11 titles, and while all titles are important, there are four that typically are of heightened interest to public registrants: Titles I, III, IV, and IX.

- Title I: The PCAOB is born

The first title of the Act established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to oversee the public accounting firms and ultimately protect investors. Essentially, the PCAOB audits the auditors.

- Title III: Corporate accountability at the highest level

Title III elevated corporate responsibility with the §302 requirement that Chief Executive and Chief Financial Officers must now personally attest that “financial information included in the report, fairly present in all material respects the financial condition and results of operations of the issuer”. In other words, the “I didn’t know about it” response is no longer a viable excuse for those at the top. We see the exact language in exhibits 31.1 and 31.2 of a registrant’s periodic reports.

- Title IV: Refined and modernized reporting

Within Title IV, §404 created the requirement for management’s assessment of internal control over financial reporting (ICFR). Fundamentally, ICFR processes and activities (internal controls) govern the transparency, completeness, and accuracy of the financial reporting data included in public filings.

- Title IX: The PCAOB carries a big stick

Intricately tied to §302 mentioned above, Title IX’s §906 further drives home the concept of corporate accountability at the highest level with new white-collar crime sentencing guidelines for those corporate officers who either failed to or willingly/falsely certified their financial reports. For the first time, both fines and imprisonment for INDIVIDUALS were penalties available for use by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Compliance with SOX

While the phrase “SOX compliance” typically, brings to mind adherence to §404 mandates, §302 and §906 disclosures are equally important to feed §404 results and vice versa.

Keeping in mind that §302 and §906 are directed more to individual principal officers, and §404 results encompass the entirety of the organization, we will focus the rest of our SOX primer on §404.

§404 is split into two parts – §404(a) and §404(b), and all public registrants, no matter the filing status, are required to comply with §404(a), which is management’s assessment of ICFR.

Let me repeat that: All public companies must comply with SOX §404(a).

Management must make a definitive statement at year-end (and update each quarter-end) noting whether their ICFR is both designed and operating effectively. Companies must also retain enough evidence to support that conclusion.

Further, depending on the filing status of the public registrant, public market float, etc., §404(b) could trigger, and the company’s external audit firm would also be required to issue a separate audit opinion on the company’s ICFR.

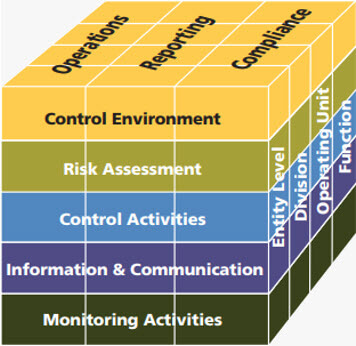

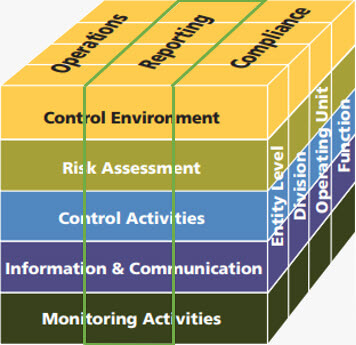

If Management’s Assessment under §404(a) is the test of compliance, the measuring stick is the COSO Framework.

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission was organized in 1985, “to help organizations improve performance by developing thought leadership that enhances internal control, risk management, governance and fraud deterrence.” The initial COSO – Integrated Framework was published in 1992. It was revised and reissued in May 2013, and it is now commonly referred to as COSO 2013. Included in the five core elements shown in the COSO cube, COSO 2013 incorporates 17 principles and 79 points of focus.

As part of a company’s §404(a) assessment, in addition to determining that an entity’s controls are designed and operating effectively, management must now make a statement that the 17 COSO principles are also “present and functioning” as part of their §404(a) assessment.

Deficiency evaluation and reporting

At the end of the day, management must report any deficiencies. PCAOB’s Auditing Standard 2201 (AS 2201) defines the different levels of deficiencies (control deficiencies, significant deficiencies, and material weaknesses), and the reporting/communication requirements vary depending on the level of deficiency identified.

- Control deficiencies must be reported to management

- Significant deficiencies must go to both management and the Audit Committee

- Material weaknesses must be publicly reported in an entity’s Form 10-Ks and Form 10-Qs

The PCAOB advises that if there are one or more material weaknesses within a company’s ICFR, the ICFR cannot be considered effective. AS 2201 further tells us that “the severity of a deficiency does not depend on whether a misstatement actually has occurred but rather on whether there is a reasonable possibility that the company’s controls will fail to prevent or detect a misstatement.”

This is an important distinction: whereas the traditional substantive financial audit focuses on actual errors found, audits and assessments of ICFR focus both on actual errors as well as the total potential for error. If an error or misstatement is found during the substantive financial audit, the external auditors will immediately turn to ICFR to determine which control, or set of controls, failed. This could then lead to a reportable event.

Engage in a SOX compliance program now

SOX very specifically focuses on the Reporting slice of the COSO cube.

One of the main purposes of SOX is to provide transparency to the investing public. Are all transactions completely AND accurately disclosed in the company’s financial statements and footnotes? Is the financial information readily available such that a reasonable investor could understand and make a well-informed decision?

Now that you know a little more about SOX, I suspect these questions are flooding in:

- What are the benefits of SOX compliance?

- How do I get started building a SOX compliance program?

- When should I get started with SOX compliance?

- How should I budget for SOX compliance?

- Is there any way to automate the SOX compliance process?

I hope you enjoyed this SOX primer.