It was early 2002, and I was a Manager in the Houston office of Andersen when Enron collapsed. We all knew something truly terrible was coming, but in my wildest imagination, I would not have foreseen the domino effect of that bankruptcy. The ensuing upheaval and impacts on not only the accounting profession, but also on my life and the lives of my many of my friends and colleagues caught us all off guard.

These events literally changed the way we all do business today.

Once Arthur Andersen was indicted, things really started moving quickly. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX or the Act) was passed in 2002. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) was born, and with it, the era of auditing and public disclosure reform had officially begun. Transparency of reporting and disclosure through both management’s and the external auditor’s assessment of internal control over financial reporting (ICFR) became the name of the game. The external audit firms were now being audited themselves. The point to all of this was to drive change. And how it did…

I went from being a Manager at Andersen to being on the forefront of first-generation SOX implementations for several Houston companies. We were starting from scratch – a blank sheet, if you will – and we were all muddling through trying to figure out the best way forward.

So, that was then. This is now.

Dear reader, if you feel like this is a lot of history to process, I’m right there with you. If I were sitting in your seat, though, I’d want to really understand the relationships between the key players driving these changes as well as those impacted by these changes. How might these historical events impact me and my business twenty years later?

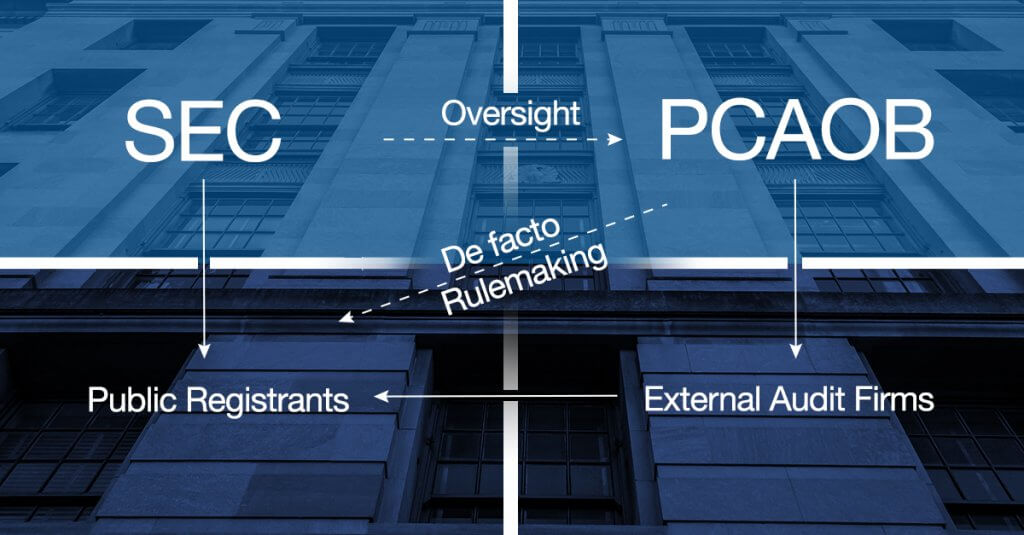

What a great question! I’m so glad you asked! Let’s look at the interactions amongst the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the PCAOB, the external audit firms and the public registrants.

Fun Fact: Did you realize that the PCAOB has been driving change to public registrants’ behavior without direct oversight to said public companies?

To set the stage: although the SEC and PCAOB are separate entities, the SEC does have oversight authority over the PCAOB. The SEC also directly governs and provides guidance and regulation to public registrants. This is nothing new. We have seen this since the 1930s. In 2002, the SOX Act established the PCAOB to monitor and govern the external audit firms. At the SOX Act’s inception, public registrants were not required by the SEC to comply with the provisions of SOX or to be accountable to the PCAOB. However, in support of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the SEC issued SEC Rule 33-8238. This rule, effective since August 2003, required all public registrants to adhere to the SEC’s new rules regarding ICFR or risk getting sanctioned. The SEC now had the hammer to enforce SOX on the public company side. Similarly, the PCAOB continues to drive change to the external audit firms, who must comply with the PCAOB’s standards or face consequences themselves.

The detail that the investing public may not realize though is that by driving change in the external audit firms’ behavior, the PCAOB is also creating de facto rulemaking for the public registrants.

We see this clearly through the inspection report process. When the external audit firms receive their annual PCAOB inspection reports, issues that are called out in that report typically become “hot topics” for the firms for the remainder of that audit and beyond. The firms must respond to the inspection report and prove to the PCAOB that they have remediated the issues identified. This often-times results in going back to the auditee and actually modifying the auditee’s processes and controls so the firms can appropriately audit the new and improved information (which then becomes subject to PCAOB inspections again).

PCOAB Staff Audit Practice Alert No. 11 (SAPA No. 11) is another example of the PCAOB driving change to the public registrants. Amid many other topics, SAPA No. 11 goes into great detail and guidance on evaluating and testing management review controls and determining the completeness and accuracy of system-generated data and reports. Even though there hasn’t been corresponding SEC guidance to enforce these two concepts, public registrants have had to put procedures in place in order to satisfy their external auditors so the audit firms can, in turn, prove their compliance with PCAOB standards. All this leads to several important questions:

- In which direction should these lines of influence run?

- Is there too much duplication of responsibilities?

- Are the waters between the SEC and the PCAOB too muddy?

- What is the best protection of the investing public?

To reiterate, the SEC does have broader oversight over the PCAOB, and by extension the external audit firms, however, the SEC is currently not in the business of inspecting audits or writing new audit standards. In February 2020, there was a flurry of activity from the White House proposing that the SEC should absorb the PCAOB. Not surprisingly, there were strong opinions on either side of the debate. For now, it appears that we are sitting in status quo on that topic.

Obviously, the events of twenty years ago changed the course of my career, as well as those of my colleagues. My perception of regulatory requirements and the intended (as well as unintended consequences) was certainly impacted. Because of SOX and the PCAOB, public companies enact business differently now. Companies certainly report the results of their business VERY differently now. I have no doubt changes will continue to come as we move through the next twenty years.